|

| MARK LYONS / ARTS AND EXHIBITIONS INTERNATIONAL; |

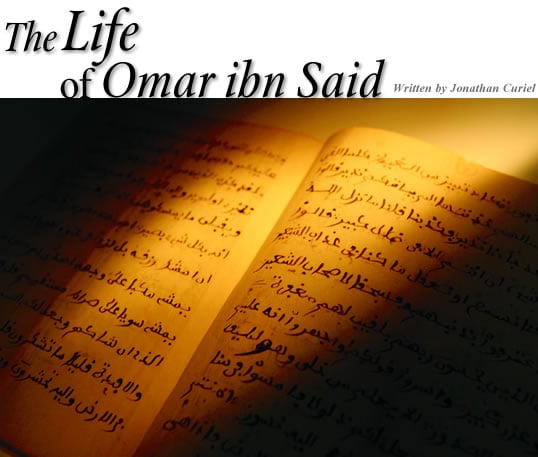

| Said’s 15-page manuscript became well-known soon after he penned it in 1831. Though translated several times, the original was lost in the 1920’s and only recovered in 1995. |

|

| ARTS AND EXHIBITIONS INTERNATIONAL |

| The traveling “America I AM” exhibition has brought new attention to Said and other aspects of African-American history.. |

t’s a summer night at the Civic Center in downtown Atlanta, and the guests, dressed in suits and evening gowns, walk amid glass cases displaying artifacts from America’s slave period. There are the tall, wooden “Doors of No Return” from a 17th-century slave-trading fort in Ghana. There is a plantation’s whip. There are iron shackles. And there is a hush around these objects; they bring tears to the eyes of some visitors.

t’s a summer night at the Civic Center in downtown Atlanta, and the guests, dressed in suits and evening gowns, walk amid glass cases displaying artifacts from America’s slave period. There are the tall, wooden “Doors of No Return” from a 17th-century slave-trading fort in Ghana. There is a plantation’s whip. There are iron shackles. And there is a hush around these objects; they bring tears to the eyes of some visitors.

At a case titled “Cultural Gifts From Africa,” the mood changes to upbeat. Among the objects it displays is a small, yellowed, 15-page manuscript written in Arabic. Its owner, Derrick Beard, tells passersby that it was written in 1831 by a Muslim scholar, a slave from West Africa, named Omar ibn Said, who was more literate than many of the slave masters he encountered in the Carolinas. Listeners tend to repeat the same interjection: “Really?”

Beard is used to it. Said’s brief autobiography, The Life of Omar ben Saeed, is the only one known to have been penned in Arabic by an American slave. The manuscript’s inclusion in the “America I AM: The African American Imprint” exhibition, which has toured the United States since early last year, is giving new audiences a firsthand look at a document Beard says “has more relevance today than it did in 1831.”

Beard is used to it. Said’s brief autobiography, The Life of Omar ben Saeed, is the only one known to have been penned in Arabic by an American slave. The manuscript’s inclusion in the “America I AM: The African American Imprint” exhibition, which has toured the United States since early last year, is giving new audiences a firsthand look at a document Beard says “has more relevance today than it did in 1831.”

Despite being enslaved by Christians, Said saw the importance of co-existence between Islam and Christianity in America. Addressing his words directly to Americans—but also indirectly to Muslims—he states that, despite the existence of the institution of slavery, there are nonetheless good people in the United States, notably his owners, whom he calls “a very good generation.” Beard sees Said’s manuscript as the first plea for religious co-existence written by a Muslim in America. Said had lived for 61 years when he wrote it; he had been a slave for 24 of them.

|

| UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL |

| One of two known portraits of Said, this daguerrotype was made in the 1850’s, when Said was about 80 years old. The other portrait, an ambrotype, appears on this issue's Table of Contents. |

“This manuscript is important because here’s a man who’s advocating having an interfaith dialogue,” says Beard, a collector of African–American history who acquired Said’s autobiography at a 1996 auction. “What else could be more appropriate to bring to the public today?”

For almost 200 years, those familiar with Omar ibn Said have debated how complete or genuine his supposed conversion to Christianity was. Said began his autobiography with the 67th surah of the Qur’an, Al-Mulk (“dominion” or “ownership”). Starting, as do all surahs but one, with Bismillah (“In the Name of God…”), its text continues, “Blessed be He in Whose hands is Dominion; and He over all things hath power….” Said’s meaning is clear: It is God who holds sway over creation.

Compared to other slaves, Said was treated well by his owner, James Owen, a prominent North Carolinian whose brother had been governor. Said was excused from manual labor on the plantation belonging to Owen, “who does not beat me, nor call me bad names,” he wrote. “During the last twenty years I have not seen any harm

at the hand of

Jim Owen.”

From his retention of Arabic—which even after decades in America he could write complete with the diacriticals that indicate short vowels—to his relatively friendly relationship with the Owen family, everything about Said was exceptional, and this drew public attention to him across the United States during his own lifetime, too. In the 1820’s, Francis Scott Key, who authored America’s national anthem, sent Said an Arabic-language Bible, hoping it would help convert him to Christianity. Newspapers wrote about Said, including one article from 1825 that described Said as “good natured” and speculated that he had been a prince in Africa, because of his “dignified deportment.” Around the mid-1850’s, when Said was over 80 years old, a daguerreotype of him was taken, followed a few years later by an ambrotype. These images, like those made of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, cemented the public’s perception of Said as an important African–American figure. That perception grew especially after 1995, when Said’s manuscript, thought to have been lost in the 1920’s, re-emerged in Alexandria, Virginia, from a trunk discovered by descendants of Howland Wood, a noted numismatist who once owned the autobiography.

|

| COURTESY OMAR IBN SAID FOUNDATION |

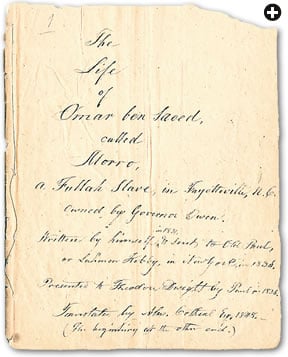

| The English-language title page added to Said’s autobiography offers details about how Said’s story was disseminated. |

The re-emergence prompted new attention to Said’s words and called forth fresh insights into his 94-year life. In the first years after Said wrote the manuscript, the Arabic experts who examined it were mainly missionaries or evangelists who gathered from it little more than proof of Said’s conversion to Christianity. Yet Ala Alryyes, Yale associate professor of comparative literature, is among those who say Said left important clues that testify otherwise—not the least of which is the manuscript’s opening surah. Alryyes’s book “O, People of America”: The Arabic Life of Omar Ibn Said, A Muslim American Slave is due to be published this year.

Said’s is not the only Muslim American slave narrative, but most of the other authors dictated their words to intermediaries who wrote them down in English. These include Job “Ayuba” Ben Solomon, whose account dates to 1734; Ibrahim Abd ar-Rahman (“the Prince Among Slaves”) in the 1820’s; and Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua in 1854.

It is significant, says Alryyes, that Said wrote himself in a language that demonstrated that he had been literate, even learned, before he was enslaved.“He offers a window into the antebellum world of slavery that is quite different from our standard, ‘normal’ view of slavery,” Alryyes says. “Other slaves acquired their literacy from their masters. Muslim slaves—because they read the Qur’an—had some literacy.”

Muslims comprised upward of 20 percent of African slaves brought to the United States, and like Said, a number of them impressed white Southerners with their proficiency in Arabic and their desire to maintain their observance of Islam’s requirement of five daily prayers. Both of these traits humanized them in the eyes of their owners—sometimes sufficiently to lead the owners to infer they were Arabs or noble Africans deserving of better treatment than other slaves, according to historian Allan D. Austin, who authored two books on the subject. What made Said more exceptional still was his maturity: When a warring African army captured and sold him in 1807, he was already 37 years old.

Born in Futa Toro (“the land between two rivers”), in what is now northern Senegal, Said came from a large, prosperous, pious family. In his Life, Said wrote that he “continued seeking knowledge for twenty-five years,” learning from his brother Muhammad and two other “shaykhs,” a word that can mean “learned men.” He claimed 15 siblings, and he waxed proud of his adherence to Islam in Africa—ablutions, prayers and alms “every year in gold, silver, harvest, cattle, sheep, goats, rice, wheat and barley.” He was, Austin says, “a scholar and a teacher.”

In the United States, Said was initially taken to Charleston, South Carolina, where he was sold to “a small, weak, evil man called Johnson, an infidel who did not fear God at all.” Johnson forced him to hard labor. “I am a small man who cannot do hard work. I escaped from the hands of Johnson after a month,” wrote Said. On foot for another month, he finally went to Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he saw a church, and he went inside to pray. “A young man saw me,” wrote Said, and two men with “many dogs” walked Said 12 miles to the “big house called jeel” (jail) in Fayetteville. There, after “sixteen days and nights,” he was bought by James Owen, whose brother was a former governor. Said spent the rest of his life with Owen’s family, even turning down overtures from colonizers who offered to help him return free to Africa—if he would go there as a Christian evangelist.

Like many other Muslim slaves in the antebellum south, Said was under powerful pressure to adopt his master’s religion. By 1831, Said was attending church and reading the Bible—in Arabic. However, his written emphasis on Quranic surahs convinces Alryyes that Said “was playing an in-between game,” professing enough Christianity to pass as a convert without denying Islam.

To bolster his point, Alryyes points to two Muslim slaves who won back their freedom. Born in what is now central Guinea, Ibrahim Abd ar-Rahman was repatriated after 40 years of slavery, thanks to diplomatic intervention by Morocco. When he returned to African soil in 1829, he renounced his conversion to Christianity. Similarly, in 1836 Lamine Kebe, who was a teacher in Guinea before enduring 30 years of slavery, reclaimed his Muslim roots after sailing to Liberia with the help of the American Colonization Society.

It is thanks in part to Kebe that we have Said’s words today: After Kebe received his freedom in 1834, but before his departure to Liberia, Said sent him the manuscript of his autobiography. Kebe passed it on to an abolitionist named Theodore Dwight. Since then, it has been translated three times, most recently in 2000 by Alryyes.

|

| WILL AND DENI MCINTYRE |

| Fayetteville tax accountant Adam Beyah also serves as an imam at Fayetteville’s Omar ibn Sayyid mosque. He is one of few people to have sought out the site and the few remains of the Owen plantation. |

To Beard, “everything [Said] writes and looks at is from an Islamic perspective. Even before he writes the Lord’s Prayer, he contextualizes it with the Fatiha (“The Opening”), the first chapter of the Qur’an. He writes that first, then he writes the Lord’s Prayer. There’s a clear reason for that: He believes the Fatiha has pre-eminence over the Lord’s Prayer.”

The night I interviewed Beard and saw Said’s manuscript behind glass was the opening night of the “America I AM” exhibition in Atlanta. The night had the feel of an Academy Awards ceremony. By special invitation, guests heard live African music and speeches (paraphrasing W. E. B. Du Bois, organizer Tavis Smiley asked, “Would America be America without its Negro people?”), then walked through an exhibition whose entry mirrored those of traditional mud-and-timber buildings in West Africa. Images of famous African Americans adorned the walls, from Frederick Douglass to Barack Obama—and including Omar ibn Said.

It’s not only here that Said is remembered, but also in southeastern North Carolina. A few years ago, Adam Beyah, a member of a Fayetteville mosque named the Masjid Omar ibn Sayyid, drove about an hour south to the small town of Bladenboro, where “Owen Hill”—Said’s plantation—had been located. Beyah and his companions were seeking Said’s grave, but they found that the plantation had disappeared, covered over by smaller, subdivided properties. “We were driving down the street, and we saw a lady in the yard,” says Beyah. “We pulled over and she asked what we were looking for. We told her, ‘Omar.’ She said, ‘Oh, you’re talking about the Prince?’”

She pointed Beyah to a nearby property, which they explored until they found “remnants of an old house and some grave stones,” says Beyah. “I’m not going to say it was Omar’s grave. I don’t know whose grave it was.”

She pointed Beyah to a nearby property, which they explored until they found “remnants of an old house and some grave stones,” says Beyah. “I’m not going to say it was Omar’s grave. I don’t know whose grave it was.”

According to research by Thomas C. Parramore, a North Carolina historian and professor who died in 2004, Said’s tombstone, which read “Omar the Slave,” disappeared many years ago. Today, people who want to honor his life often come to the Masjid Omar ibn Sayyid, where Beyah or others can show them Said’s daguerreotype and tell his story.

|

| WILL AND DENI MCINTYRE |

| Today, the Owen plantation is unmarked and largely overgrown. |

|

| WILL AND DENI MCINTYRE |

| Atop of a small knoll that residents today say is “Owen Hill” stand these ruins of a family burial plot, near which Omar ibn Said is believed to have been buried—but of his grave there remains no trace on the land. |

Said died in 1864, one year before Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment that officially abolished slavery in the United States. Beard believes Said knew that his autobiography would be read for many years. “It’s almost as if he wrote this manuscript for today,” Beard says.

Including Alryyes’ forthcoming work, more than 50 books have now devoted at least some attention to Said. In North Carolina, Beyah says, public-school history books describe Said’s life in detail. In addition to Fayetteville’s mosque, a boarding school in New Haven, Connecticut, has taken its name from Said. In the future, Beard hopes a movie version of Said’s life might be produced.

Alryyes points out that Said composed his autobiography shortly after the slave rebellion led by Nat Turner. Did antebellum slave owners, asks Alryyes, look to Said’s Life for reassurance that not all slaves were blood-thirsty avengers? In prefacing his autobiography with a surah from the Qur’an, was Said inspired by ex-slave David Walker, whose 1829 “Appeal” was a riveting abolitionist document that similarly cited God’s dominion over all? Or was Walker somehow inspired by ideas already in circulation thanks to Muslim slaves like Said? Such questions, Alryyes says, may never be answered, but by raising them, Alryyes hopes to broaden understanding of the context of Said’s autobiography.

Africa and America, freedom and slavery, Islam and Christianity, all coalesced in his brief 1831 manuscript. “To see his written word is just fascinating and beautiful,” says Mark Lach, senior vice president at Arts and Exhibitions International, which designed the “America I AM” exhibit. “To have it right in front of you is a privilege.”

|

Journalist Jonathan Curiel (www.jonathancuriel.com) is the author of Al’ America: Travels Through America’s Arab and Islamic Roots (2008, New Press), which won an American Book Award. As a Reuters Foundation Fellow at Oxford University, he researched Islamic history; as a Fulbright Scholar, he taught at Punjab University in Pakistan. |