Spaces for All

For the Teacher's Desk

Built environments can foster community within cities and neighborhoods and change how we view the world.

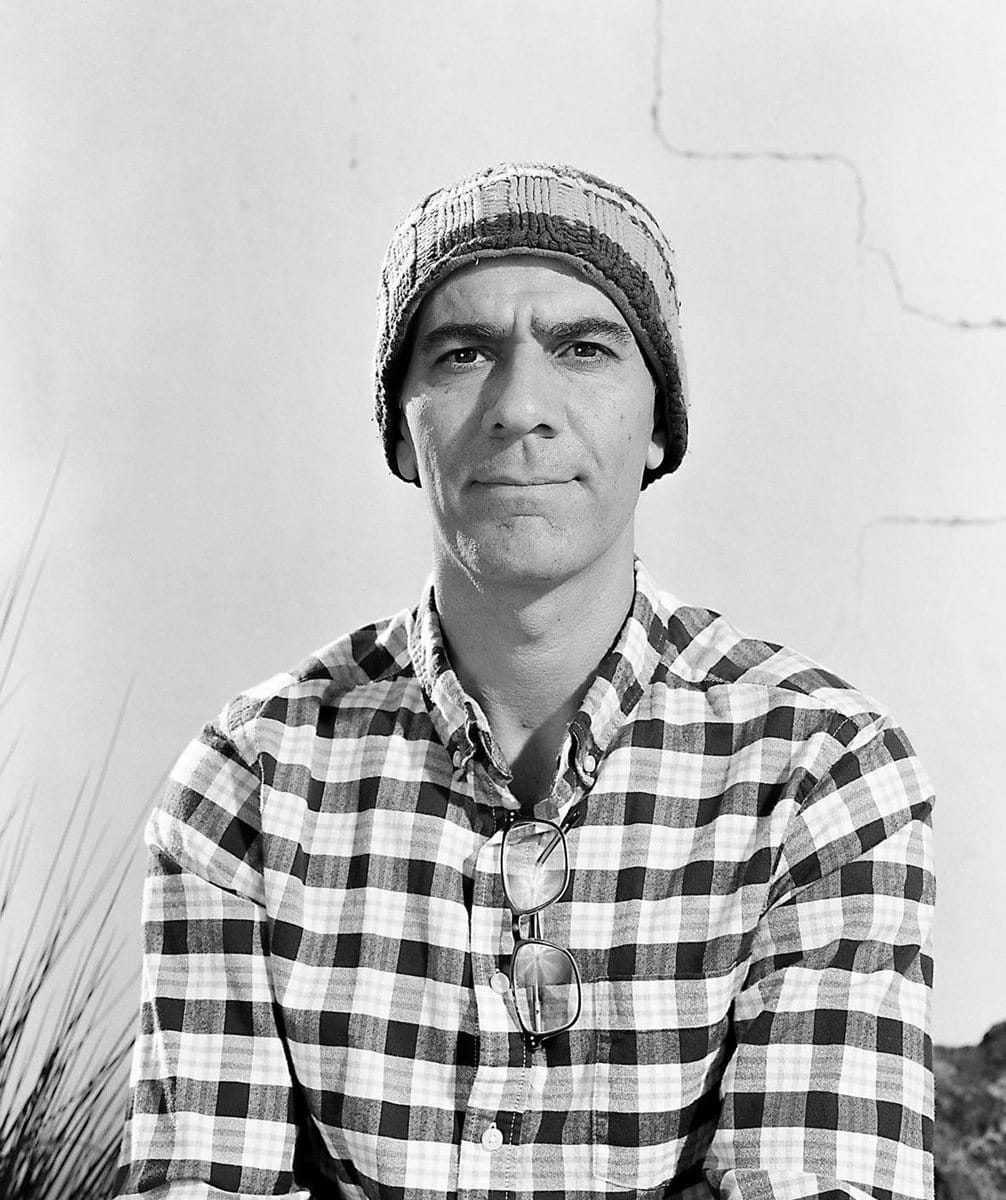

Growing up skateboarding, Amir Zaki felt drawn to skateparks—particularly for the sculptural environments the concrete ramps and ledges evoked. To Zaki, professor of photography and digital technology at the University of California, Riverside, these structures do more than just echo the shapes of hills and valleys found within landscapes. Instead, they are manmade, constructed to bring people together.

“I like this idea of a kind of sculpturally sculptural space, a space that mimics nature but had a purpose for skateboarding,” he says.

Zaki’s photographs form the basis of one of the latest lessons in AramcoWorld’s Learning Center, "Skate Parks in the Abstract,” built from the AramcoWorld story, Amir Zaki’s "Sculpture of Skateparks," in the June 2024 issue. Through the lesson, educators can challenge students about their perspective of public spaces in their communities and ask them to document alternative ways people can view them.

Examples of spaces designed for public use abound. For example, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead gained fame for his iconic designs of Central Park and elements of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, which feature manicured pathways that meander from quiet meadows to wild woods. Olmstead crafted his environments as spaces where people could immerse themselves through walkways, on lawns, and across bridges fashioned throughout urban spaces.

Educators don’t need to draw on Olmstead’s designs to encourage students to think about how public space can change communities—they only need to have students look in their backyards.

From small parks to town squares, these areas, typically found globally in many communities, can help teachers take Zaki’s work and make it locally relevant to their classes.

Challenging Views

Zaki often uses digital tools to manipulate his images, enhancing the point of view he wants to present. He might remove graffiti, present on a structure, or even people who may appear in a shot.

“Sometimes I make work that intentionally will change it in a way that makes it look more alien or more foreign,” he says.

One of Learning Center’s suggested activities from the story about Zaki’s photographs asks students to consider how an abstract image may not reflect a space in its reality. For example, a skatepark rendered by Zaki transforms into a space devoid of active skateboarders who typically congregate inside, morphing into a space that mirrors images of broken pottery he exhibits with his work.

Educators could encourage students to locate spaces within their communities and then compare a realistic image of the space and one that’s more abstract, mirroring Zaki’s photographic style if they choose. Or students could seek out built environments and urban landscapes and capture them with their unique artistic approach.

“There’s something about taking a look around your neighborhood or community,” says Anton Schulzki, interim executive director of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). “What are some of the places that have been built that created connections?”

Encouraging Connection

Walter Hood, chair and professor of landscape architecture and environment planning and urban design at the University of California, Berkeley, suggests educators ask students to first talk about the spaces they inhabit on their own.

One group may talk about a garden, while another may share about the community that meets at a specific street corner in their neighborhood. Teachers can have classes capture those places through photography or a written paragraph, considering how people use them—and why.

“The spaces already exist,” says Hood, also creative director of the Oakland, California-based Hood Design Studio, which designed landscapes for The Broad Museum Plaza in Los Angeles, the International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, and the De Young Museum Gardens in San Francisco among other projects. “It’s the people who bring a culture to those spaces,” he says.

While some architects and designers construct public spaces with community-building in mind, others organically appear for unknown reasons. A corner of a parking lot where students buy snacks after school can transform into a gathering spot, much like a coffee station in an office building.

As Stuart Butler, the Washington, DC-based scholar in residence at The Brookings Institute, notes, these are spaces that occur by happenstance, where “you casually interconnect with people,” he says, and foster connections.

Schulzki likes the idea of students transforming public spaces for their use, such as taking over a corner of a park or any neighborhood space for lunch, for example. In doing so, they’re folding into civic life and shaping their community, he says.

“That builds the notion of action, of civics, because then as they grow up, they come involved in the community, whatever their community happens to be,” he says.

That local focus runs central to Zaki’s approach. He feels compelled, he says, to document public spaces he can find in his immediate environment, places close to his home rather than rarified locations far away. His upcoming work, for example, looks at public libraries, places where people come to read, work and study.

As educators ask their students to community spaces within their neighborhoods, classes can feel they’re following in the artist’s footsteps.

“I don't like the idea of private spaces, or spaces that only certain people get access to because they can pull some strings,” Zaki says. “I'm going to walk out my front door, and I'm going to observe the world around me.”

Other lessons

Training Somaliland's Next Generation of Caregivers: Identifying the Thesis and Supporting Arguments

Women Studies

East Africa

Conduct a close reading of Somalian pioneer midwife, educator and public health figure to identify evidence for a thesis.

Palermo’s Palimpsest Roads: A Study in Multicultural Cooperation

Architecture

Art

History

Europe

Define multiculturalism, and explore how different metaphors affect our understanding of diversity.

Building a Mudhif: Overcoming Challenges to Achieve Sustainable Architecture.

Architecture

Environmental Studies

History

Americas

Levant

Read how a community overcame challenges to replicate a traditional reed structure dating back 5,000 years.